Samuel Pappo was born on May 28, 1917 in Constantinople, in the Ottoman Empire. One of my earliest memories was in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, on September 20, 2000, tossing handfuls of petals and earth into the chasm of his grave.

He was the fifth child of Lazare Pappo and Elise Yeshua Alguadiche – the fourth to survive. His siblings were brothers Salomon and Salvator; a baby, Regine, had died in 1914, to be followed by another sister named in her honour. After Samuel would follow the youngest of the family, Fortunée, born in 1919.

The Pappo family had come from Andrinople and Haskovo before settling in Constantinople during the first World War. Before that, they had lived in Italy, in Livorno. In Ancona, on the Adriatic coast, a monument stands, with the names of dozens of Jews who were murdered by papal decree for refusing to convert to Christianity in the year 1555. One Joseph Pappo was among them.

Sammy, as his family called him, grew up attending school in the Bulgarian town of Varna, a seaside resort known for its beaches on the Black Sea. He and his siblings were educated in French, which would come to serve them well later on in life. Sammy’s father, Lazare, ran an import/export business; he was, at one point, jailed for it.

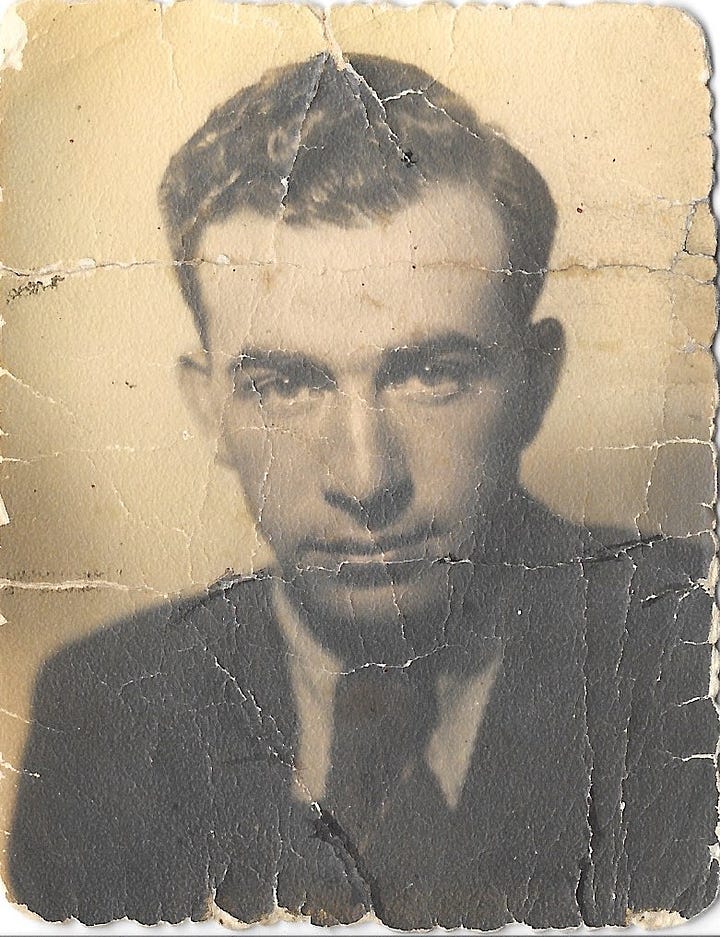

The Pappos’ family photo, taken on June 8, 1927, shows a stoic, well-to-do family. The eldest sons, with their long, fluffy hair combed back, stare directly into the camera, as if emulating the on-screen smoulders of John Gilbert and Rudolph Valentino. Their mother, Elise, cocks an eyebrow at the lens, unsmiling in her dark dress and marcelled waves. Sammy sits in a chair beside his father, with Fortunée propped up on one side, her hand resting on her brother’s shoulder for support. He wears a suit with short pants, the brass buttons of his jacket gleaming in the bright lights. His hair is cropped short, and he holds a penetrating gaze as he steadies his younger sister, the pleated skirt of her black sailor suit falling just above her knee. Standing in the back is a teenage Regine, wearing a cropped wool coat and striped sweater, her curly bob hitting right at the cheekbone. The whole family is frozen, stone faced, in their best clothes and polished leather shoes.

Staring back at Sammy’s face, I think of all the stories I have heard from throughout his life, and all of the things that the ten year old boy looking out at me will become. In 1940, at the age of 23, he would leave Bulgaria on board a ship bound for British Mandatory Palestine. Unable to afford the boat’s fare, the story goes that he joined on as a member of the crew, an opportunity he owed to his familiarity with Morse code.

That same ship, the S.S. Orion, also carried his future wife, Herzalina Jonatan, and her entire family. Upon landing in the British territory, the Pappos and Jonatans were taken to Atlit Detention Camp, just south of Haifa, where they were interned by the British for a number of months. Their chance encounter, which preceded the signing of the Tripartite Pact by little more than a year, not only ensured their safety from the Nazis, but also marked the start of a relationship that would last until the end of Herza’s life. I still have the orders of deportation, issued by the Palestine Police Force in 1942, saved among my grandparents’ records. They would not leave the country until two years after Israel’s independence, when they came to Canada in 1950.

In Israel, Sammy became many things: a soldier, a husband, a father, and a member of the burgeoning country’s Radio Technician’s Association. His love for his century’s rapidly advancing achievements in technology has lived on through generations – every time I play a record, the sound comes through the same Fisher tube amplifier that he purchased in 1950s Montreal. His handwriting is still scrawled across the inside of the unit, marking each filament in place. Every time I shoot a roll of film, I gaze through the same viewfinder that he shot our family’s photos with. Ever scrupulous, he saved each manual and instruction sheet that came with his Leica M2 – I can still see the price he paid for each lens and accessory, counted down to the last cent in the currency of 1958.

Growing up, the photo I saw the most of my grandfather was taken on the day of Herza’s death: September 8, 1997. My father stands in the centre of the photo, hair grey at the temples but eyebrows still dark. He holds an infant in his left hand, a bundle of white blankets with a shock of dark hair and baby pink socks. I was born a week earlier, on September 1st – enough time to let the beginning of my life and the end of my grandmother’s briefly overlap. In the coming years, visions of her would fill my dreams, like us together in a florid garden, picking red and yellow roses. It was so vivid, I was convinced it was something we had really done.

Behind my father stands Sammy, with his arms wrapped around my parents’ shoulders. His eyes are still as sharp and perceptive as they had been when he was a boy. My mother stands smiling beside him, youthful and glowing. She’s only 25 in this photo – two years younger than I am now. My aunt Lisa and cousin James stand to my father’s right, James wearing a cord necklace and a t-shirt from the University of British Columbia. He and my mother are just a few years apart.

Herza sits in the foreground beside her grandchildren, on the last day that her photo would ever be taken. My parents tell me that throughout our whole visit, she would not stop fussing over the new baby. She thought I was too tiny and too cold. I was given my middle name, Hailey, as a tribute to her.

Recently, somebody asked me where I came from. I was unable to offer a simple answer. “Canadian” or a list of countries of origin would not suffice. I think about these photos of my family, and the stories they tell. What they represent. How I come from people who have been displaced, over and over and over again. From people whose citizenship or lack thereof have lasted for indeterminate periods in their lives. Who were subjected to ghettos, and detention camps, and the jizye tax, and who sought to create prosperous new lives despite it all. Who were the recipients of generations of exile and upheaval, simply for being born Jews.

Originally begun as part of a writing workshop with Aaron Henne, November 2024. Inspired in part by conversations with Rachael Cerrotti, curator, storyteller, and author of “We Share the Same Sky” and Along the Seam. I’ve stolen the title of this piece from her - it’s the dedication she made out for me in my copy of her book. My grandparents’ stories are ones that I’ve thought about writing for over a decade, and that I’m finally attempting to put down on the page. As family historian, I owe much of my reference material to my great-aunt Regine, whose research in the 1970s has greatly aided my own.

💙